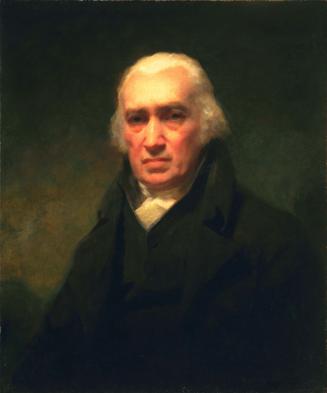

Jean (Robertson) Pitcairn

Maker

Henry Raeburn

(British, 1756-1823)

SitterSitter:

Jean (Robertson) Pitcairn

(British)

Collections

ClassificationsPAINTINGS

Dateca.1790's

Mediumoil on canvas

Dimensionscanvas: 35 1/4 × 27 in. (89.5 × 68.6 cm.)

frame: 46 × 38 1/2 × 4 in. (116.8 × 97.8 × 10.2 cm.)

DescriptionSeated three-quarter length in leather covered armchair in plain interior. Nearly full face, hands clasped lightly in lap. Dressed in brown dress with white apron, white bouffant fichu, black net scarf with ruffled edge, and high white mob cap decorated with pink and blue ribbon.

Credit LineThe Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens. Gift of W. Averell Harriman

Label TextJean Robertson was the daughter of Alexander Robertson, provost of Dundee, Scotland. Her birth and death dates are unknown. She married John Pitcairn, Provost of Dundee, and they had three sons and three daughters. Raeburn is esteemed as much for his acute analysis of human character as for his deft handling of paint. Here, he reveals his sitter's strengths and foibles in a deceptively simple portrait. As befits the elderly wife of a prominent judge, Jean Pitcairn is dressed soberly in a gown of plain brown silk. Her neck and chest are entirely covered by a starched white linen bouffant fichu, into which she has tucked a bit of frilled chemisette as a modesty piece. Her lap is equally well covered by a starched white linen apron. The concern with propriety expressed by her costume is wedded to an evident interest in fashionability. The tight fitting of her long sleeves (embellished with an understated frill), and the ruffle-edged black net scarf crossed over her shoulders and tied at the waist reflect the styles in vogue during the 1790s. Most striking of all is the tall cotton bonnet, which adapts the old-fashioned mob cap of the 1780s to the narrower hairstyles of the following decade. Similar bonnets appear in several of Raeburn's portraits of older women, but few rise to such a height. The bonnet's outlandish silhouette and precious ornamentation (consisting of a generous double row of fluted muslin edging and a pink-and-green-striped satin bow) add winsome touches of gaiety and extravagance that undercut the portrait's overall tone of sobriety. The implicit suggestion of personal vanity is borne out by the dark curls that frame the sitter's face; they are very likely "false fronts," locks of hair that women attached under their caps to compensate for their own thinning supply.

The acute perception that enabled Raeburn to pierce his sitter's character also helped him to seize on the essentials of her appearance with speed and certainty. He generally set to work directly on the canvas, blocking out the picture in broad strokes. The final composition was attained by steadily building up this initial oil sketch. Later in his career, Raeburn was criticized for lack of finish, but in this early portrait transitions in the contours of the face and drapery are articulated with a relatively fine touch. Close handling and observation also characterize the detailing of the ruffles of the hat, bouffant, and cuffs, as well as the individually itemized tacks of the chair. The liveliness of Raeburn's brushwork is dissipated to some extent by these fussy details and they also undermine the psychological focus that characterized his paintings in subsequent decades. The diffuse, frontal lighting employed here also disappears from later works that adopt more concentrated and dramatic effects of light and shadow.

Other aspects of this picture herald qualities for which Raeburn would later become well known. The fichu and apron are blocked in simply with square, flat strokes of the brush, and the gradations of black and grey created by the net bouffant (as it stretches to transparency or gathers in opaque clusters over the gown and fichu) are masterfully observed. The stark presentation of the sitter against a simple, shadowy background helps to focus attention on the person before us.

In tandem with the present portrait, Raeburn carried out a pendant of Jean Pitcairn's husband, John, seated in a matching black leather arm chair and facing in the opposite direction. The paintings were first separated in June 1914. Less spectacular than the full-length show-portraits that Raeburn was simultaneously producing for exhibition in London, modest paintings such as this pair accounted for the majority of his practice. The premium they place on accurate and forthright presentation differentiates them from much English painting of the period but held strong appeal for patrons in Raeburn's native Scotland.

Status

Not on viewObject number44.150