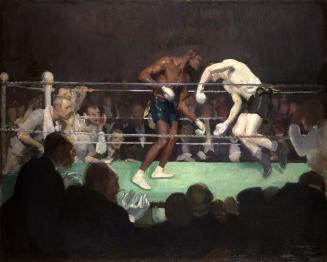

Shoveller Held by Her Trainer Will Chifney

Maker

Benjamin Marshall

(British, 1767-1835)

SitterSitter:

Will Chifney

(British, 1784 - 1862)

Collections

ClassificationsPAINTINGS

Date1819

Mediumoil on canvas

Dimensionscanvas: 40 1/4 × 50 1/4 in. (102.2 × 127.6 cm.)

frame: 49 × 59 × 4 in. (124.5 × 149.9 × 10.2 cm.)

SignedSigned and dated lower right: B. Marshall pt. 1819

Credit LineThe Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens

Label TextWill Chifney was born at Newmarket in 1784, the elder of two sons of the famous jockey Sam Chifney, Sr., and his wife, a daughter of the Newmarket horse trainer Frank Smallman. Deemed too big to ride at five feet, seven inches (two inches taller than his father), Will was trained from childhood in the arts of stable-keeping and horse-training. His astute judgment of horses and severe methods of training brought extraordinary success, and canny betting generated enormous profits. Chifney spent money lavishly, however, and with the encouragement of his wife, Mary Clarke (daughter of the professional backer Vauxhall Clarke), he built a grand house to outstrip that of his brother, the jockey Sam Chifney, Jr.. The two brothers established a stable of racehorses that included Priam, whose victory in the Derby Stakes of 1830 brought them winnings of approximately £18,000. Heavy losses on the Duke of Cleveland's horse Shilelagh in 1834 exacerbated Will's mounting financial difficulties and he was obliged to sell his fine house and stables and move to London in reduced circumstances. He died at Pancras Square, aged seventy-eight, on October 14, 1862. He appears in this portrait holding the reins of the racehorse Shoveller, a bay filly foaled in 1816 by Scud, out of Gooseander. Bred and owned by Thomas Thornhill (1780-1844) of Riddlesworth Hall, Norfolk, Shoveller ran her first important race on April 16, 1819, winning a 200 guinea prize at Newmarket. Victorious in the Oaks Stakes at Epsom on May 28, 1819, she gained His Majesty's Plate of 100 guineas at Newmarket on April 10, 1820, and came in second in the Gold Cup race at Newmarket on May 3, 1820. She failed to place on several other occasions, however, and after taking second in a minor race at Newmarket on May 8, 1821, she was retired. A prominent patron of the British turf, Thomas Thornhill commissioned this portrait to commemorate his second major racing victory: the triumph of his bay filly, Shoveller, in the Oaks Stakes at Epsom in 1819. Shoveller had not been favored to win, but through the skillful riding of Sam Chifney, Jr., she slipped past Lord G.H. Cavendish's Espagnolle by little more than a head. The previous year Thornhill had commissioned Marshall to paint his chestnut colt Sam (half-brother of Shoveller), winner of the 1818 Epsom Derby. In 1820 he would commission a third painting from Marshall, this time representing his chestnut colt Sailor (another half-brother of Shoveller), who won the Oaks that year. Thornhill had reason to be proud of winning these back-to-back championship races, an unprecedented feat in English racing history. As it happened, however, he failed to sustain this high level of achievement. None of his horses again placed in either of Epsom's two classic races, although they continued to be trained (for the most part) by Will Chifney and were often jockeyed by Will's brother, Sam. The last painting Thornhill commissioned from Marshall was of the 1823 Derby winner Emilius, which he purchased in 1824. Even then, the portrait was evidently commissioned as a hopeful speculation, and Emilius failed to live up to Thornhill's expectations.

In the present painting, as in many others by Marshall, the artist's emphasis on the underlying anatomy of the horse gives it a curiously cadaverous appearance. Marshall's excessive attention to anatomy is often chalked up to naiveté, but it seems more likely that he had practical reasons for cultivating this aesthetic. From an artistic point of view, it draws overt parallels with the anatomically sophisticated horse paintings of George Stubbs, whose death in 1806 opened a window of opportunity for Marshall. From a sporting point of view, Marshall's exaggeration of the horse's leanness signals Shoveller's fitness as a racer. Early nineteenth-century trainers and jockeys placed enormous value on the leanness of racehorses, and many attributed the Chifneys' successes to their aggressive (some said cruel) pre-race campaigns of sweating horses down to the lowest weights possible. Moreover, although the horse is shown at rest, Marshall's emphasis on its taut muscularity lends it an appearance of physical strain, suggesting its potential energy and strength. The specificity with which Marshall documented the horse's physique would have appealed to sporting enthusiasts, who assessed thoroughbreds such as Shoveller with a keenly pragmatic eye.

The horses in Marshall's paintings generally lack the palpable sense of personality with which Stubbs imbued his animals, and here, as in other instances, it is the human figures that lend the painting its psychological and narrative interest. In the foreground, Marshall established a witty contrast between the awestruck stable boy carrying Shoveller's saddle and rug, who gazes up at the horse with an earnest, almost reverential gaze, and the masterful man beside him, who holds the champion's reins while turning his head aloofly aside. Only Shoveller appears to be conscious of posing, standing patiently in profile and making direct eye contact with the viewer. The background is enlivened by Marshall's vivid rendering of an atmospheric sky, filled with broken clouds. These are painted with great freedom in a spectrum of pale pinks, purples, blues, greens, and yellows. Stronger notes of color are provided by the innumerable tiny figures lining the race course, crowding into the spectators' stand, and dashing past in carriages and on horseback. The bold contrasts in scale--with hundreds of lilliputian bystanders glimpsed between Shoveller's monumental legs--enhance the dramatic quality of the horse's presentation.

The actual identity of the horse became garbled within a few years of Thornhill's death. In his book The Post and the Paddock of 1857, Henry Hall Dixon mentioned Marshall's prior portrait of the racehorse Sam, adding, "In the following year he painted one of Shoveller to match it, in which Will Chifney holds the mare by the head, while a lad is rubbing her down." The boy rubbing down the horse actually appears in Marshall's portrait Sailor (illustrated above), painted not in 1819, but in 1820. Dixon's error was compounded when all four of Marshall's portraits for Thornhill sold at Christie's in 1920, and the present painting was identified as Portrait of "Sailor," standing on the Downs, held by the trainer, with a groom holding a saddle. The fact that the horse in the present painting is a bay (ruddy in color with dark points) and female (lacking the male genitalia that Marshall usually made visible in portraits of colts) rules out identification with the chestnut colt Sailor. This evidence, together with the date of 1819 (the year of Shoveller's Oaks victory) inscribed with Marshall's signature in the lower right corner of the painting, are all factors supporting identification of the horse as the bay filly Shoveller.

Confusion has also sprung up concerning the identity of the man holding Shoveller's reins. In 1922 Walter Shaw Sparrow misidentified him as the "Owner, Sir Henry Thornhill," and when the painting was acquired by The Huntington in 1958, he was described more plausibly as Thomas Thornhill. Even this identification is specious, however. Thornhill was notorious for his tremendous girth; by March 1825, he weighed nearly 335 pounds, and his size had become fodder for caricatures in which his massiveness provided a humorous foil to the diminutive frame of his favorite jockey, Sam Chifney, Jr. Far from appearing obese, the man in the present painting is remarkable for his slenderness, accentuated by the cut of his coat. Given the acute perceptiveness of Marshall's portraits, it seems improbable that he would have falsified Thornhill's appearance so completely when a more subtle form of flattery might have sufficed. He certainly did not shy away from representing physical quirks and imperfections. Stocky figures recur in his paintings, and in a portrait of 1806, he faithfully documented the phenomenal girth of his close friend Daniel Lambert, the sideshow fatman (Leicestershire Museums and Art Galleries).

If not Thornhill, the man holding the reins in this portrait could only be Will Chifney, whose masterful training, as much as his brother Sam's skillful riding, was credited with the success of Thornhill's horses. Having paid tribute to his jockey in the portrait commission of 1818, Thornhill may have wished to recognize the contributions of his trainer the following year. It is somewhat unusual to find a trainer dressed in the elegant uniform of top hat, cut-away coat, stock, and vest that Marshall generally reserved for owners (thereby distinguishing them from jockeys in their caps and silk jackets, and from grooms and trainers in their squat hats and heavy greatcoats). However, there are other inconsistencies in Marshall's use of this sartorial vocabulary, and here, the elegant dress probably honors Will Chifney's unique status within the social hierarchy of the race course. His professional success, great wealth, and intimacy with owners such as Thornhill seem to have elevated his stature well above that of the average trainer. Moreover, he and his brother Sam were known for emulating the opulent ways of their patrons, rather than the modest habits of their colleagues. One writer has described them as "the first men to raise the status of their respective professions." The man holding Shoveller's reins matches descriptions of Will Chifney as "a tall spare man, whom no one would have connected with racing had they not known his profession and parentage," for he possessed "the air of being a clergyman or a scholar," was "solemn of expression" and "always soberly, if expensively dressed." Despite the confusion of the past, the proper identification of the portrait now seems clear, and its implications for the social codes of the time add further interest to this lively Epsom scene.

Status

Not on viewObject number58.3

George Romney

1786-1792

Object number: 11.44

John Hamilton Mortimer

ca.1763

Object number: 78.8

Angelica Kauffman

ca. 1780

Object number: 2001.11